Digitizing History: Palestine Broadcasting Service, 1936-1948

(under Construction)

under construction

INTRODUCTION

PALESTINE BROADCASTING SERVICE (PBS) AN EPISODE IN EARLY PUBLIC DIPLOMACY, 1936 - 1948

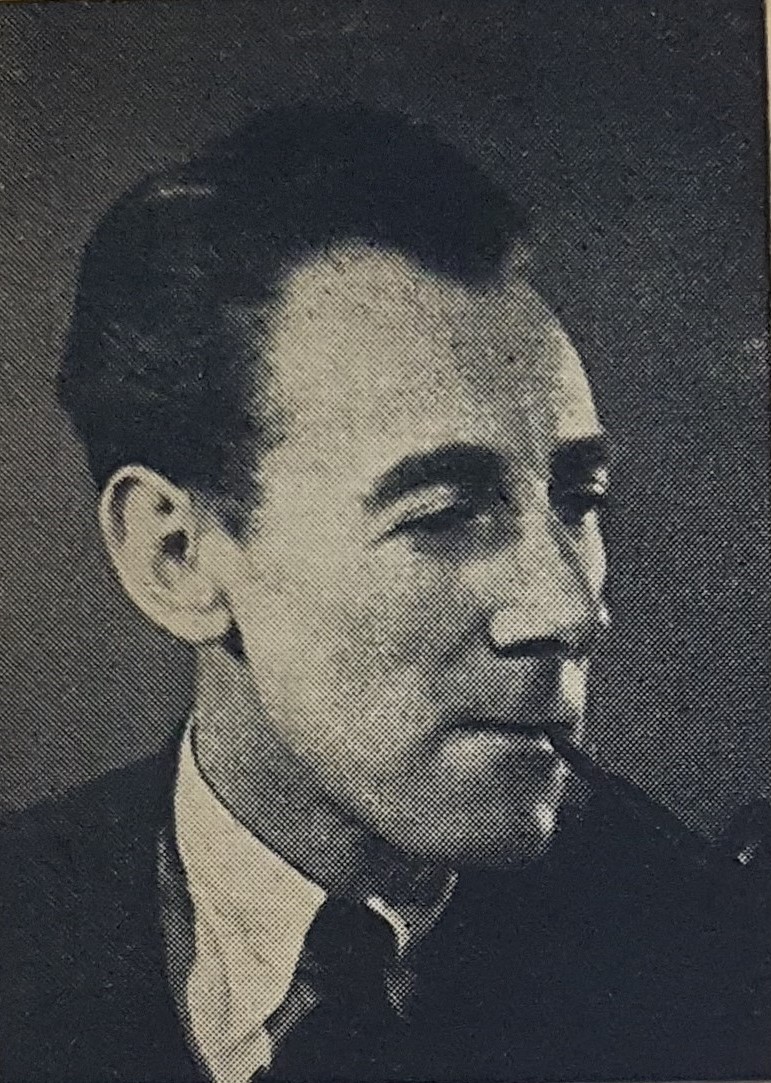

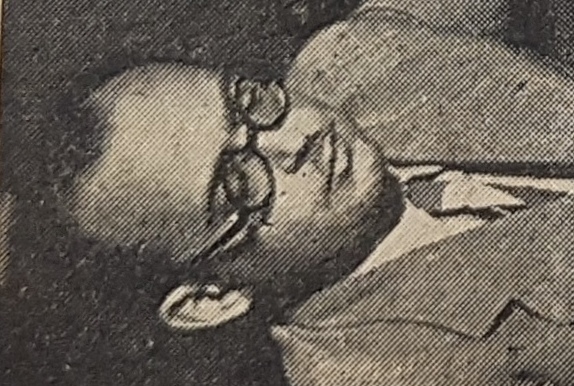

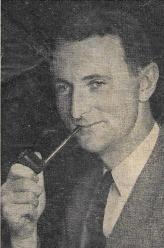

Directors of PBS Programmes / Broadcasting

|

|

|

|

|

|

R. A. Rendall

April 1936 till October 1936 |

Stephen Fry October 1936 - October 1938 |

Crawford B. McNair

1938- 1941 |

G. D. Kennedy

Deputy Postmaster General 1942-1945 |

Edwin Samuel 1945-1948 |

This website is a work in progress. It will try to reconstruct in a digitized format, the Palestine Broadcasting Service (PBS) and its experiment with public diplomacy 1936-1948. It will do this by focusing on the programs and publications produced by the PBS, including daily schedules. It will take into consideration the people behind the scenes and in front of the microphone.

It's easy to dismiss the PBS as just another colonial institute, but that would be doing those that served or worked in it a great disservice. The PBS was not just pioneering radio broadcasting it was pioneering what could later be termed "public diplomacy".

While there is agreement today that there is no single agreed definition of public diplomacy, there is a working definition for it, which is:

"The transparent means by which a sovereign country communicates with publics in other countries aimed at informing and influencing audiences overseas for the purpose of promoting the national interest and advancing its foreign policy goals."

(see webpage for University of Southern California (USC) Center for Public Diplomacy)

1. TRANSPARENCY

TRANSPARENT MEANS OF COMMUNICATION: How transparent, how opaque was the PBS? From 1945, PBS broadcast a weekly program entitled Between Ourselves" (בינינו לבין עצמנו Bein-aiy-nu Levain Azmainu). These programs were always delivered by the senior management team, British and local: Edwin Samuel, Rex Keating, Mordechai Zlotnik, Director of Hebrew Programs; Karl Salomon, Musical Director, and Yeshayahu Klinov.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Edwin Samuel, Director of Broadcasting delivered the broadcast, in English, on Fridays, while Mordechai Zlotnik, the Director of Hebrew Program, Karl Salomon, Musical Director and Yeshayahu Klinov, delivered either a Hebrew translation or completely different version on Saturday evening, after the Sabbath holiday. The program was a bulletin board of program, staff, and policy changes. It often included in-house management details, such as general statistics on budgets and royalties, information on the availability of training programs, among other things.

Public Feedback/ Listeners Planning Committees

The broadcasting authorities were constantly trying to develop a better product, to find out what the public thought of their broadcasts, what would the public like to see changed. To that end, the PBS established a Listeners Planning Committee. This went round the main cities and towns of the Yishuv to find out what listeners really thought of them first hand. From a public diplomacy perspective, it was exceedingly important to get to know their audience and to see whether the broadcasts were in fact influencing hearts and minds. Another way was through competitions and quizzes, requesting listeners to send in their answers to the PBS, or just to correspond with the radio station to subscribe to the publications and let them know about likes and dislikes. The staff at PBS would then have a better idea as to who was tuning in to their broadcasts

2. INFLUENCING TARGET AUDIENCES

Initially, in the planning stages, it was clear that the target audience would include both urban and rural populations. They would outreach to every nook and crannie of the land. One caveat: No Politics! That just meant not to get embroiled in local party politics, at least not directly.

As the High Commissioner Arthur Wauchope delivering the key note address at the inauguration of the Ramallah Transmitter (March 30, 1936) said (my italics):

"..we determined to establish a Broadcasting Service in Palestine, that will work for the advantage of the people both in town and country.

The Broadcasting Service in Palestine will not be concerned with Politics. Broadcasting will be directed for the advantage of all classes of all communities. Its main object will be the spread of knowledge and of culture nor, I can assure you, will the claims of religion be neglected.

As in all our activities, we shall start on a small scale but, God willing, we shall advance step by step, until we have a service worthy of the vivid and varied life of Palestine.

We shall try to stimulate new interests and make all forms of knowledge more widespread. I will give you two examples in both of which I have a deep interest.

There are thousands of farmers in this country who are striving to improve their methods of agriculture. I hope we shall find ways and means to help these farmers and assist them to increase the yield of the soil, improve the quality of their produce, and explain the advantages of various forms of cooperation.

There are thousands of people in Palestine who have a natural love of music, but who experience difficulty in finding the means, whereby they may enjoy the many pleasures that music gives. The Broadcasting service will endeavour to fill this need, and stimulate musical life in Palestine, so that we may see both Oriental and Western music grow in strength, side by side, each true to its own tradition..."

In other words, the target audience as initially envisaged included: town and country; all classes (Britain had then a very class oriented society); religion; science and technology; education; culture; and the arts, particularly classical and local music. That "the Broadcasting Service in Palestine will not be concerned with Politics" just meant not concerned with local political parties, such as Mapam/Mapai, etc.

But the News broadcasts were always important (see sidebar).

Ruth Belkine

Chief News Editor, PBS

"The Golden Voice of the PBS"

3. BRITAIN'S NATION INTEREST/FOREIGN POLICY GOALS: To promote unity between Britain and and the diverse communities of Palestine (Jewish, Arab and Christian) and to promote unity between the same diverse communities of Palestine themselves.

Very quickly they added into their program schedules that included news and announcements; Language learning on the air (English, Arabic and Hebrew); astronomy; international and current affairs; industry and trade; the national economy; labour and social issues which included women affairs; programs for youth (sport and physical fitness programs); education (schools and institutes of higher education); book reviews; national campaigns (health and road safety, among others) ; entertainment. and radio technology.

Radio was an outreach tool par-excellence. The various departments of the mandatory government could link to their Jewish and Arab counterparts in ways unheard of before the advent of radio. These counterparts included the Vaad Leumi, which was, for all intents and purposes, the Jewish parliament (knesset) - in-waiting; The Histadrut (labour movement) ; and Non-Governmnet Orgnizations (NGO's) such as WIZO: Women's International Zionist Organization; and Hadassah: The Women's Zionist Organization of America ; roads, railways and fledgling civil aviation authorities, among many others, the list goes on.

They could develop a relationship with these institutions, either to tap them for local experts to talk about their professsional subjects -so long as they had a good radio voice, and steered clear of what was regarded as controversial areas, as stated in contract with the PBS from 1936:

" The Artist further warrants that any such manuscript work as aforesaid shall not contain anything political, libellous or slanderous character or anything calculated to bring any government, race, religion, community or sect into disrepute."

All the more important during the war years.

Or, to bring over experts from Britain, America, Western Europe, or the British Commonwealth. As Wauchope had stated "to spread knowledge and culture...to stimulate new interests."

Sound Recordings

There are, frustratingly, very few audio recordings that remain from the programs, in the public domain. But recordings there were! As Rex Keating and Ruth Belkine (the newsreader) put it...

"Rex Keating: A favorite expression duiring the war was "Off the record", but that wouldn't apply to broadcasting - much of which is "on the record" quite literally, on discs. In the PBS library there are hundreds of bits and pieces of radio programmes - excerpts from talks, plays, speeches, replays - all collected over a period of years, mostly forgotten on a few top shelves until on rare ocasions such as this, they are taken down and dusted and through the magic of modern radio are made to release their imprisoned sounds and voices from the past.

Ruth Belkine: And that's just what we are going to do now - Let the PBS tell it's own story from its own records of ten years - the narrative will be a little fragmentary in places, a little distorted in others for apparatus is not infallible and discs were sopmetimes hard to come by, particularly in the war years. Therefore, a little jerky perhaps, but interesting, as any biography of Palestine must be. So let's turn back the clock"

The First Ten Years, Rex Keating, broadcast March 30, 1946. (From Rex Keating Collection, 2/6/1, MEC Archive, St. Antony's College, Oxford).

For a study of radio that is a major disadvantage. We have to rely on the next best thing, transcripts, wherever they can be located. In some cases this is made possible by some of the transcripts of the more popular series appearing in full, excerpts, or synopsis in the PBS's publications such as Jerusalem Radio a weekly publication that started in September 30, 1938, and Hagalgal the magazine that replaced "Jerusalem Radio", starting July 22, 1943. Hagalgal started out as a fortnightly publication becoming weekly only in November 1944. In addition, transcripts of the radio programs are to be found in books and/or pamphlets, that were published as aids to following the radio broadcasts, or for those without radios to be able to learn about the programs without having to listen in to the broadcasts themselves, or who missed the broadcasts for whatever reason.

Some examples of these pamphlets/books include: Let's Speak English, by the President of the Brighter English League (24 lectures, 1938-1939); A collection of 17 lectures (in Hebrew to Jewish farmers) on agriculture by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, broadcast on PBS radio, 1937-1939;Hebrew for Yiddish speakers, by Saul Barkali (1947); Morning Physical Fitness Exercises, by Michael Ben Hanan (1948); and many others.

To be clear, the PBS was not a clone of the BBC. There were many significant differences between the BBC and the PBS. In the first place, the BBC was an independent corporation, and proud of that status, while the PBS was a British government agency, established as a department of the Post Office administered by the Postmaster-General. Secondly, there was the problem of language. The BBC may have had regional divisions to consider, but basically only one language, English, and the occasiuonal program in Welsh or Gaelic. They had one major publication flagship for its schedules, The Radio Times. The PBS in considering their target audiences had to prepare programs and publications in three languages, English, Arabic and Hebrew. This had a significant impact on the budget and hiring personnel - they had to hire people that could communicate both the spoken and written word in all of these language. They also needed translators.

Ralph Poston |

Ralph Poston, Deputy Director, Programmes, PBS wrote in the Jerusalem Radio , March 31, 1939: "So often the criticism is heard 'such and such a station cannot receive much more in licence fees than the P.B.S., yet it gives much better talks and concerts'. True, it may not receive a total which is bigger, but it does not have to divide its budget into three parts to cater for three language groups. The P.B.S. would be a much easier organisation to run if, for instance, it could spend all the money it had available for music on Western music, or Arabic or Jewish Music - but instead it is forced to divide its budget among the three programmes, a fact which critics would do well to remember and one which affects all branches of its activities. "

|

They also needed to supervise local staff to stay on message of the Mandatory Government. Trust was a major issue. This became more acute during the war years.

Edwin Samuel, who later became Programs Director, PBS, was given the job of radio censorship during the war years. He wrote about this in his book “A Lifetime in Jerusalem" (1970):

“As the newscasts themselves were drafted by the public information office throughout the war, all I had to do was to provide reliable men in the studios who switched off the broadcast if the announcer deviated in any way from the approved script. This involved no exercise of judgment but only continuous concentration, which was extremely exhausting. The radio switch censors also had to prevent any particular tune being broadcast to carry a hint (say, of troop movements) to listeners abroad. Musical request programmes were, therefore, prohibited till the end of the war. Even a mispronunciation of a word , or a stammer, or merely a cough, had to be considered as a possible means of instant communication with enemy monitors in the Balkans, or in neutral countries such as Turkey. ...

...Jerusalem was the center for the training of censors-in-charge and chief examiners for postal and telegraph censorships in other territories in the Middle East…

... by the end of the war, I had Palestinian staff in Aleppo, Baghdad, Khartoum, Eritrea and even Teheran where, believe it or not, there was a joint Anglo-Russian- Persian Censorship...."

Edwin Samuel was not totally accurate when he wrote that "Musical request programmes were, therefore, prohibited till the end of the war". However, a closer look at the daily radio schedules will show that while these request programs disappeared from the schedules from August 3, 1940, one year into the war, they were re-instated from Saturday, May 1, 1943, with the war still raging in Europe. The war would continue in Europe for another two years!

RE-ORGANIZING THE PBS By May 1945, the war in Europe was over, although there was still fierce fighting going on in the Pacific arena against Japan until September 1945. Not waiting for hostilities to end Edwin Samuel who was appointed the new director of broadcasting, June 1, 1945, immediately began to reorganize the PBS into the post-war world and the new local environment, to move away from propaganda to what we call "public diplomacy".

This was not the first time that the PBS had reorganized itself. That took place back in 1938, under Crawford B. McNair, then Acting Director of the PBS. McNair, a Scotsman, and former conductor of the BBC Northern Regional Orchestra. McNair helped steer the changes that including the establishing the weekly journal "Jerusalem Radio", and, as his first love was classical music, he was a major force in establishing the PBS Orchestra and Choral Society. He was also instrumental in bringing over to Palestine Sir Malcom Sargent, then known as Dr. Malcolm Sargent, and considered as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. Fast forward to 1945, Edwin Samuel, brought in the former war correspondent, Rex Keating, as Assistant Director of Broadcasting, PBS (1945-1948), based in Egypt at that time, to help him with the reorganizations.

The PBS management had realized the Jewish and Arab staff were like wild horses, pulling in opposite directions, and saw it necessary to separate the Arabic and Hebrew broadcasts once and for all.

On December 15. 1945, with the separation of Arabic and Hebrew to separate radio stations, the Hebrew listeners were given no choice but to change the dial on their radio to a new setting to hear the broadcasts in Hebrew. The change-over took place relatively peacefully, having communicated what was going to happen in advance. This gave the organizers freedom to pursue their respective programs without the frustration of knowing that the Jewish listeners would switch off the radio or change channels as Arabic programs came on the air while the Arab listeners would switch off or over, when the Hebrew programs were on the air.

By May 1948, the experiment was over. The new Israeli Government under the leadership of David Ben-Gurion, within the year placed Mapai (the Workers Party of the Land of Israel) members into key positions, replacing non-Mapai members, effectively destroying most of what had been learned over the past 13 years. The legacy of the PBS lives on today, mainly through its publications.

In conclusion, this site can only scratch the surface of the subject, and my hope is that it will add something, however little, to the public knowledge to this near forgotten and often misunderstood episode of history, and shine a spotlight on the pioneers of radio in Palestine, and the relationship between Britain and Israel during the Mandatory period that today we know as "public diplomacy", a ray of light in an otherwise dark era.

Leslie Smith

FURTHER READING

(1) Letter Edwin Samuel wrote to Wing Commander A. H. Marsack, BBC offices, Cairo, dated May 24, 1945 archived Rex Keating 2/7/1, MEC Archive, St. Anthony's College, Oxford.

(2) Letter Edwin Samuel wrote to Rex Keating, dated 31 May, 1945. Archived Rex Keating 2/7/1/-2, MEC Archive, St. Anthony's College, Oxford.

Stranton, Andrea, L : Jerusalem Calling: The Birth of the Palestine Broadcasting Service"

| צור קשר: lesliesmith466@gmail.com |